The Chapel’s Rich History

Before the chapel was built, the Middlesex Hospital had little non-clinical or non-administrative space. Wood-panelled boardrooms hosted chaplaincy services, but there was no space specifically designed with peace, prayer and reflection in mind. Initial funds were raised through donations, and eminent architect John Loughborough Pearson was engaged by the hospital board to design the small building in the heart of the hospital complex. Pearson had been awarded RIBA’s Gold Medal in 1880, and his designs included St Augustine’s Church in Kilburn, Truro Cathedral, Westminster Hall, Bristol Cathedral, and additions to St Margaret’s Church in the grounds of Westminster Abbey.

Construction began on the chapel’s red brick exterior in 1891, when Pearson was already nearing the end of his life. His son and apprentice, Frank, took over after his father’s death, writing to the board of hospital governors to tell them of his father’s death, and his own wish to complete the project. The finished chapel is a combination of both their designs, and reflects the influences of Gothic European architecture in the work of both men. The first service in the chapel was held on Christmas Day 1891, with an official opening ceremony by the Bishop of London taking place in June 1892.

The chapel took more than 25 years to complete. It includes more than 40 types of marble used in its finished design. In its early life, it housed candlesticks, effigies, pews and altar cloths — all purchases which were made possible through fundraising by the medical community.

The chapel hosted regular services throughout the week, led by the Middlesex’s resident chaplain. Sermons were broadcast throughout the wards over hospital radio so that those too sick to visit could be a part of the chapel’s activity. On two occasions, the BBC broadcasted from the chapel as part of a series of national hospital radio shows.

A Place of Solace

The chapel served as a place of solace, prayer and rest for staff and patients and their families. It was always open between services, and groups of different faiths (and none) from within the hospital gathered in the tiny building throughout the working week. Marriages between medical staff, or between very ill patients and their partners, took place here, as well as concerts, memorials, seasonable celebrations and choir rehearsals.

Many present-day visitors have spent time here before, whether as a medical professional, family member or patient and the memories they share contain moving descriptions of chapel life in the past. Doctors or nurses visiting to find quiet after a difficult shift; porters sitting quietly in the candlelight reflecting on a day’s work; mothers taking their first trip out of the ward with their new-borns; or families and friends returning to the chapel time after time while caring for their loved ones. This tiny chapel provided a space for the population of the Middlesex Hospital to attend to their interior lives — their needs, hopes, griefs and celebrations were routinely observed beneath its starry ceiling.

Restoration

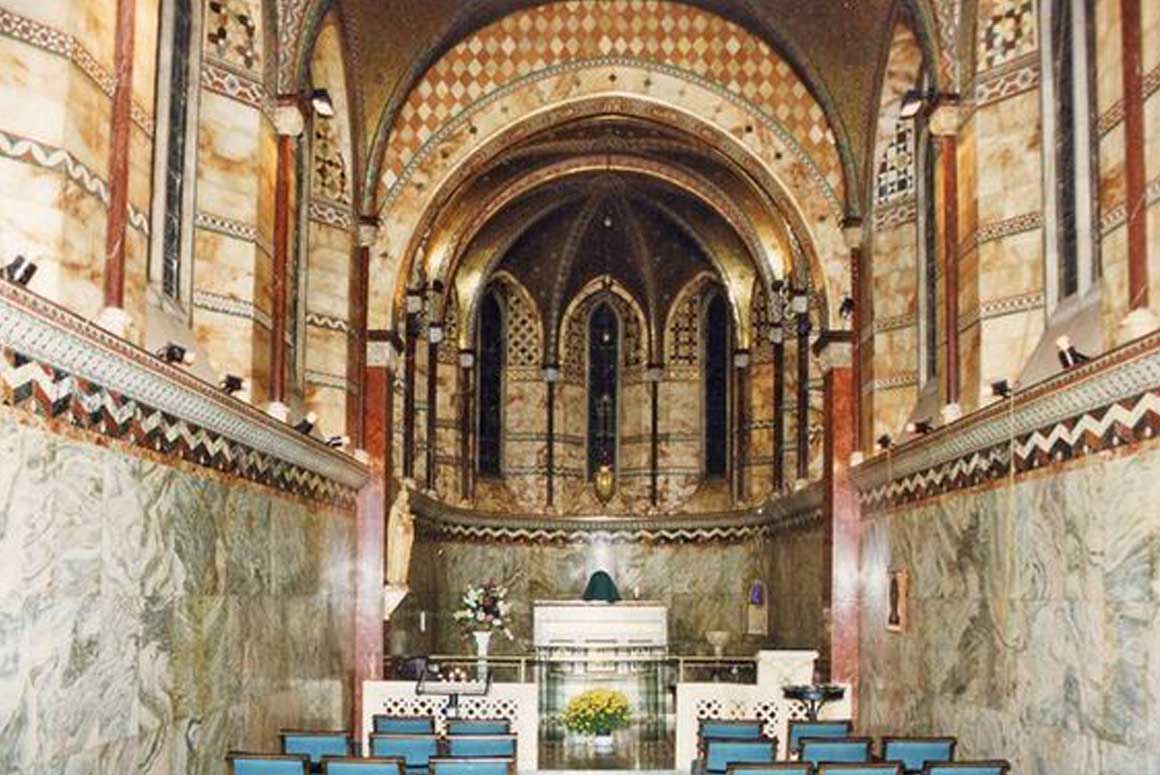

The £2 million restoration of the chapel was carried out by conservation architects Caroe & Partners between 2013 and 2015. It involved improvements to external brickwork, and extensive work on the mosaic ceiling, which had suffered greatly due to water ingress. The external roof had aged poorly, penetrated by rainwater which damaged mosaics and several marble panels. In some places, up to 70% of the ceiling tiles required re-gilding, and extensive scaffolding was erected throughout the chapel to enable restorers to access and restore designs. Pearson’s Alpha and Omega mosaics were safely removed during the installation of a modern fire safety system, and installed behind organ pipes for safekeeping. All windows were removed and renovated off site before being reinstalled, and the restoration also provided the building with a modern electricity supply as well as amenities to ensure its function as a standalone building.

Exploring the Chapel

As you enter

The viewing door on your left as you enter the building provided access from the main hospital corridor into the chapel. The ante-chapel (or narthex) contains incised marble plaques commemorating the lives of many staff from a long period of Middlesex history. Plaques could be bought for around twenty guineas each – money which went towards completing the chapel. Memorials include Major Ross to whom the building is a memorial, Lord Webb Johnson who supported the chapel’s initial construction, and Dame Diana Beck who was the first female neurosurgeon in Europe. Among medical staff, other roles commemorated are those of chaplains, maintenance foremen, stewards and secretaries, who were an essential part of the hospital’s infrastructure. In the small corner corridor, there are plaques to nurses who were killed by typhoid and scarlet fever outbreaks in the hospital in the late nineteenth century, which severely impacted hospital staff numbers.

The ceiling

Although the golden mosaic ceiling over the nave is one of the chapel’s most breathtaking features today, it was not the first ceiling designed for the building. John Loughborough Pearson’s original design consisted of open oak ceiling in the main space, with golden mosaic vaulting only over the chancel, including a simple Alpha and Omega mosaic above the altar. Pearson began replacing the wooden vaults with full mosaics in 1929. He reportedly used to ask himself of each of his designs “Does it send you to your knees?” Even though it was his son who completed the ceiling’s dazzling design, the mosaics surely meet Pearson’s awe-inspiring aims. Early mosaics were completed by Robert Davison’s Decorative Art Studio based in nearby Marylebone, and later in the 1930s, Maurice Josey worked on further designs.

The baptistery

The semi-circular baptistery was built in memorial to Sir John Bland Sutton, a surgeon and lecturer at the hospital. The blue gradient in the baptistery with accompanying angels draws comparisons to existing baptisteries in the Emilia Romagna region of Italy, Palermo and Venice. Its four windows depict soldier saints: Joan of Arc, Saint George, Saint Alban and Saint Martin, and together these windows form a memorial to the dead of World War I. The majority of the windows in the chapel were fabricated by Clayton & Bell, and comprise dedications to medical school staff and the hospital board. You can read a report into our Stained Glass and other Beautiful Objects on the Middlesex Hospital website.

The font

Both the font and the front of the organ loft are carved in Verd Antique, and the font sits on a base plinth of carved Grand Antique. The four evangelists are depicted on the corners of the font, and its inscription is a Greek palindrome roughly translating as ‘wash clean my sins, not just my face’ which can also be seen inscribed on a holy water vessel outside Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.

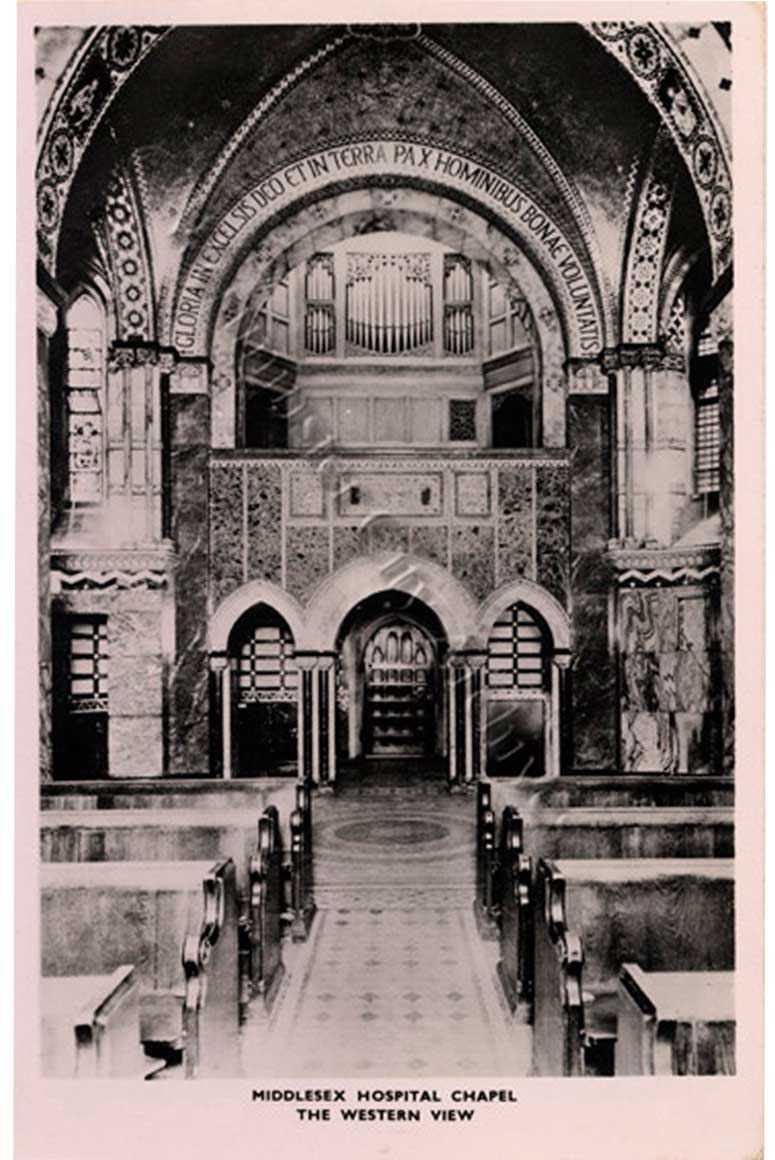

The organ

Over the organ loft, mosaics spell out the Latin phrase ‘Gloria in excelsis deo et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis’ which translates as ‘Glory to God in the highest, and peace to all men on earth’. The chapel’s original organ, a thirteen stop Lewis & Co instrument which was removed from the building in the early twentieth century, was used regularly by an organist engaged by the hospital. It was replaced by an electric Allen organ which is still functioning and is occasionally used for weddings or concerts in the chapel. Opposite the baptistery is a large mosaic roundel depicting St Barnabas, and vaults over the nave feature mosaic busts of the 12 apostles. At the top of Pearson’s alabaster red marble columns, one can see a common design motif throughout the chapel of foliage and repeated stiff-leaf capital designs.

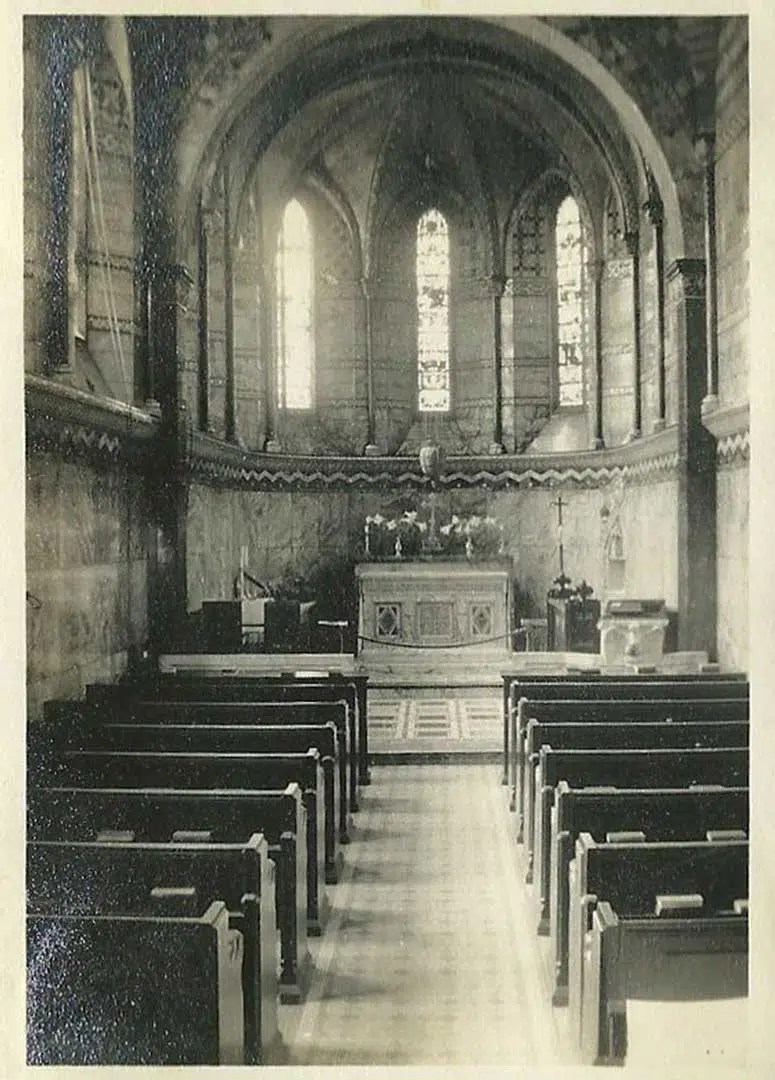

The altar

The chapel’s marble altar was designed by Frank Loughborough Pearson, and was installed in around 1905. Alabaster is used regularly throughout the chapel, with both the piscina, balustrade and eagle lectern carved in it. Near to this, there is a simple incision in the marble wall commemorating the lying-in-state of poet and writer Rudyard Kipling in the chapel after his death at the Middlesex Hospital.

The Middlesex Hospital

The hospital began as the Middlesex Infirmary, opening in the 1740s. It consisted of two small terraced houses in Windmill Street, off Tottenham Court Road. The original buildings were leased from Mr Goodge, a local landowner, and were later converted to accommodate 15 beds. The Middlesex was founded as a charity for the ‘sick and lame of Soho’ but included the slums of Seven Dials around St Giles-in-the-Fields in its care. For six centuries, London only had two hospitals: St Bartholomew’s and St Thomas’. In 1719, the Westminster was founded, followed in succession by Guy’s, St George’s, The London and in August 1745, The Middlesex, so called because London at that time was part of the county of Middlesex.

New Hospital Site

When open maternity beds were added in 1747, the first ever in a general hospital, the total number of beds increased from 15 to 25. The demand for beds was considerable and the number increased again to 40. Some patients had to be accommodated in neighbouring houses. A new site was found in Marylebone Fields on the estate of Mr Charles Berners and a lease was signed for 999 years at £15 a year. On 15 May 1755, the Earl of Northumberland, President of the Hospital, laid the foundation stone on the current site.

The hospital’s finances became difficult the Napoleonic Wars began, with many of the wards becoming empty due to lack of money. The hospital opened a ward for sick refugee clergy, who occupied one ward until 1814. By 1815, the hospital had 179 beds and by 1915, had been further enlarged by extending the wings to the street and adding a third floor.

The chapel was built as a memorial to Major Alexander Henry Ross, MP, Chairman of the Board of hospital governors for 21 years.

The chapel′s architect John Loughborough Pearson, one of the foremost gothic revivalists of his day, was commissioned in the late 1880s by governors of The Middlesex Hospital.

Demolition

In 1924, the original building was declared structurally unsafe and demolished. The cost of rebuilding was solely covered by donations and within three years, on 26 June 1928, the Duke of York, later King George VI, laid the foundation stone. The West Wing opened in 1929 and the Crosspiece and East Wing in 1935. Indeed the Duke of York returned to open the completed building on 29 May 1935. The hospital had been completely rebuilt, on the same site and in stages, without ever being closed. It has been paid for by more than £1 million of donations from the public.

In 1992, the St. Peter’s Hospitals were closed down and moved into new accommodation in the Middlesex Hospital, which itself was merged into the University College London Hospitals NHS Trust in 1994.

Associations

While part of the Bloomsbury Health Authority in the 1980s, the Middlesex Hospital was also associated with St Peter’s Hospital, Soho (urology); St Paul’s Hospital, Red Lion Square (skin and genito-urinary diseases); Soho Hospital for Women (gynaecological diseases); Horton and Banstead Hospitals (psychiatric disorders); Athlone House (geriatric care); and St. Luke’s (Woodside) Hospital (psychiatric disorders).

Medical School

The Middlesex Hospital Medical School traced its origins to 1746 (a year after the foundation of the Middlesex Hospital), when students were ‘walking the wards’. The motto of the medical school, ‘Miseris Succurrere Disco’, was provided by one of the deans, Dr William Cayley, from Virgil’s Queen Dido aiding a shipwreck: ‘Non ignara mali, miseris succurrere disco’ (‘Not unacquainted with misfortune myself, I learn to succour the distressed’).

University College Hospital

At the establishment of the then London University (now University College London), the governors of the Middlesex Hospital declined permission of the former’s medical students to use the wards of the Middlesex Hospital for clinical training. This refusal prompted the foundation of the North London Hospital, now University College Hospital.

The medical schools of the Middlesex Hospital and University College Hospital merged in 1987 to form the University College and Middlesex School of Medicine (UCMSM). The current UCL Medical School, which resulted from the merger of UCMSM and the Royal Free Hospital School of Medicine in 1998, still honours the Middlesex Hospital in its coat of arms.

Courtauld

The Courtauld Institute of Biochemistry of the Middlesex Hospital Medical School was opened by Samuel Augustine Courtauld in 1928, the foundation stone having been laid on 20 July 1927. Its main entrance was in Riding House Street. Courtauld also endowed a Chair of Biochemistry. Notable researchers at the institute include Frank Dickens FRS, Edward Charles Dodds FRS and Sir Brian Wellingham Windeyer FRCS (plaque holder).

Nurses’ home

In January 1929, the Queen laid the foundation stone for a new nurses’ home in Foley Street, made possible by an anonymous gift of £300,000. The home, or rather Residential College for Nurses, was opened by Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone, in June 1931. It provided accommodation for 300 people: 230 Sisters and nurses, pupils of the Preliminary Training School, as well as those attending massage and midwifery courses, and domestic staff. The building also contained the Preliminary Training School and its classrooms, recreation and smoking rooms, badminton and tennis courts and, in the basement, a swimming pool (only to be used when at least three people were present, two of whom had to be good swimmers). The oak-panelled dining room was on the ground floor and the kitchen was capable of supplying meals for 300 people at one sitting. There was also a hairdressing salon in the basement. (It was later renamed John Astor House, after the anonymous donor was identified in 1948 when the hospital joined the NHS).

Children’s ward

A children’s ward opened in 1930 on the sixth floor of the new West Wing, which had been completed in 1929. The cots were bright blue. The walls of the ward were covered with tiles illustrating nursery rhymes, which had been donated by Bernhard Baron, who had also given £10,000 to the hospital. The ward had its own kitchen and a sun balcony. Newly admitted patients were accommodated in isolation rooms, which were separated by glass panels, for three of four days until a clear medical history had been obtained.

Lord Woolavington

A block for private patients was made possible by the Canadian-born Lord Woolavington, who donated a large sum of money for this purpose in memory of his wife who had died in 1918. At this time patients could only be admitted if their income was below certain strict levels. Middle-class patients therefore could only be treated in nursing homes, which were expensive and not very well equipped. The hospital board decided to convert the residents’ block in Cleveland Street, built in 1887, and the Sisters’ Home, built a few years later, into a private wing and to build new premises for the resident house staff. The Woolavington Private Wing opened in 1934.

New Buildings

The Crosspiece and the East Wing were completed in 1935 and the new building was officially opened in June by the Duke of York. The hospital had 712 beds and had cost £1,125,000 to rebuild, entirely paid for by donations — some large and some small (one milliner in Oxford Street had collected 5,000 farthings — about £5.21). It had seven storeys and was built to the same style, with projecting wings and a crosspiece. Even the clock was replaced in the pediment, now with a gold face instead of a plain one. The entrance hall was panelled with Robinson’s paintings representing Acts of Mercy. Beyond the hall was a terrace which led to an open courtyard, surrounded on its four sides by the hospital.

The main x-ray department, gifted by Mr W.H. Collins, a London businessman, began working on the day the hospital opened. A radiotherapy department, the gift of Mr E.W. Meyerstein, a retired stockbroker, was almost complete. Both benefactors gave a further £50,000 each to endow these departments. Mr Stafford Bourne, one of the founders of the department store Bourne and Hollingsworth, donated the funds for an operating theatre, which subsequently bore his name. A new fracture unit was planned.

During World War II, the top three floors of the hospital were emptied of patients for safety reasons, and were damaged by bombs. As a teaching hospital, the hospital was in charge of one of the sectors of the Emergency Medical Service, with its advanced base hospital at Mount Vernon Hospital.

Founding of the NHS

In 1948 the Middlesex Hospital joined the NHS and became the lead hospital in a teaching hospital group which included its convalescent home at Clacton-on Sea, the Hospital for Women in Soho, St. Luke’s-Woodside (a psychiatric hospital in Muswell Hill) and the Arthur Stanley Institute for Rheumatic Diseases (previously the British Red Cross Clinic for Rheumatism). In 1958, the hospital acquired Caen Wood Towers in Highgate for use as a post-operative recovery and geriatric unit (its name was changed to Athlone House, after the Earl of Athlone, a former Chairman of the Board of Governors). The hospital was entirely funded by voluntary subscription until the founding of the NHS in 1948.

Hospital closure

In 1980, following a reorganisation of the NHS, the hospital together with University College Hospital and several smaller specialist hospitals in the area came under the control of the Bloomsbury Health District. In 1984 the in-patients’ building of the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital in Great Portland Street closed and services moved to an upgraded ward on the fifth floor of the Middlesex Hospital.

Princess Diana opened the Broderip and Charles Bell Wards in 1987. They were the first in the United Kingdom dedicated to the treatment and care of patients with AIDS and HIV-related illnesses. In 1992, St Paul’s, St Peter’s and St Philip’s urology hospitals closed and moved their services into newly refurbished ward accommodation at the Middlesex Hospital. The hospital closed in 2005 and all services moved to the new £422m PFI-built University College Hospital in Euston Road. The 16-storey tower there has been named the Middlesex Tower in honour of the hospital.

John Loughborough Pearson

Before the chapel was built, the Middlesex Hospital had little non-clinical or non-administrative space. Wood-panelled boardrooms hosted chaplaincy services, but there was no space specifically designed with peace, quiet and reflection in mind. Initial funds were raised through donations, and architect John Loughborough Pearson was engaged by the hospital board to design the small building in the heart of the hospital complex. Pearson had been awarded RIBA’s Gold Medal in 1880, and his designs included St Augustine’s Church in Kilburn, Truro Cathedral, Westminster Hall, Bristol Cathedral, and additions to St Margaret’s Church in the grounds of Westminster Abbey.

Construction began on the chapel’s red brick exterior in 1891, when Pearson was already nearing the end of his life. His son and apprentice, Frank, took over after his father’s death, writing to the board of hospital governors to tell them of his father’s death, and his own wish to complete the project. The finished chapel is a combination of both their designs, and reflects the influences of Gothic European architecture in the work of both men. The first service in the chapel was held on Christmas Day 1891, with an official opening ceremony by the Bishop of London taking place in June 1892.

The chapel took more than 25 years to complete. It includes 17 types of marble used in its finished design. In its early life, it housed candlesticks, effigies, pews and altar cloths — all purchases which were made possible through fundraising by the medical community.

The chapel hosted regular services throughout the week, led by the Middlesex’s resident chaplain. Sermons were broadcast throughout the wards over hospital radio so that those too sick to visit could be a part of the chapel’s activity. On two occasions, the BBC broadcasted from the chapel as part of a series of national hospital radio shows.