‘Will it Bring them to their Knees?’ The Fascinating Evolution of the Fitzrovia Chapel

In this article, we reflect on the fascinating life of the Middlesex Hospital’s chapel, moving from its days in the courtyard at the centre of the hospital though to its current iteration as a community arts space and events venue. The urban and social context of such a rare and unique place is key to understanding how best to put it to work for the community it serves – and we share how the history of the building and our experience as a part of the Fitzrovian community is hugely influenced by the creative and social opportunities in the area past and present.

The Middlesex Hospital began its existence in 1745, in two adjacent residential houses on Windmill Street, paid for by Mr Goodge of Goodge Street Tube fame. The purpose of the hospital at that time, which ran as an annual subscription, was to provide care for ‘the sick and lame of Soho’. The demands on this tiny institution swiftly grew. In 1747 it became the first infirmary in England to provide a lying-in unit for expectant mothers – and the need for its services far outstripped the space and resources available, so enquiries were made to begin finding new premises which could accommodate the growing hospital. In 1755, the foundation stone for the new hospital was laid by the Earl of Northumberland at the three acre site on Mortimer Street which was to be the home of the Middlesex for the next 248 years, and the first version of the Middlesex was built, the central block opening in 1757.

Blake, Paine and Burke

William Blake was born at 28 Broad Street, Soho just ten years after that foundation stone was laid. Accounts from that time describe there being little more than fields and market gardens to the north. This was an important period in the evolution of the area with initial developments by Charles Fitzroy, Lord of the Manor of Tottenhall. The east and south sides of Fitzroy Square were designed by Robert Adam in 1794 and survive in their original form, in Portland stone. Fitzroy Square was built for the upper classes, but artists, writers and thinkers were already drawn to the area. It was cleaner than Soho but offered more freedom than neighbouring areas. Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man was published during his residence at 154 New Cavendish Street, in reply to Edmund Burke (author of Reflections on the Revolution in France), who lived at 18 Charlotte Street.

Over the years, more wings and sections were added, but remaining in the heart of the rectangular complex was a small courtyard. This central courtyard was used at different times as a small garden, equipment and refuse store, and at one point held a temporary mortuary. By the middle of the nineteenth century, the pastoral needs of the patients and staff community had not yet been observed with a purpose-built space for reflection, contemplation, prayer, or simply some quiet in the midst of a fast-paced and large institution, as the hospital was by this point.

Progress and poets

The world was changing. Fitzrovia as it would much later be known, was almost unrecognisable from Blake’s childhood. Creativity continued to thrive from the exquisite craftsmanship of furniture in the locality and the painters Walter Sickert, Ford Maddox Brown, and Whistler producing great work from homes in Fitzroy Square. French poets Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine lived for a time in Howland Street. Fitzrovia became a hub of Chartist activities after the Reform Act 1832 and hosted working mens clubs including the Communist Club at 49 Tottenham Street. Progress was keenly felt with the industrial revolution, the locomotive boom, vaccinations for the poor, income tax during peacetime, the Public Health Act, the Crimean War, The Origin of the Species, advancement in married women’s rights. This pioneering hospital in one of the busiest parts of the capital was at its centre.

Thoughts were turning to wellbeing. During the 1880s, Swiss physician Maximilian Bircher-Benner began pioneering nutritional research and the YMCA launched as one of the world’s first wellness organisations, with its principle of developing mind, body and spirit.

By 1890, the absence of a space for nurturing and hosting the difficult moments of the hospital community’s collective experience was keenly felt by key members of the Board of Governors of the hospital. For some time, suggestions of a memorial to the late Major Ross MP, who had been chair of the weekly board of governors of the hospital for 21 years had been made. Archived letters exist from the Secretary Superintendent of the hospital to close friends of Major Ross asking if they would wish to contribute to a memorial fund, suggesting that ‘… such a memorial shall if possible, take the form of a chapel for the Hospital. This is a want that has long been felt and was an idea in which Major Ross himself took a warm interest, bringing it up on more than one occasion’. With this memorial and a desire to provide for the pastoral needs of the hospital community in mind, the board began to make plans and assemble funds to commission such a place.

Architect appointed

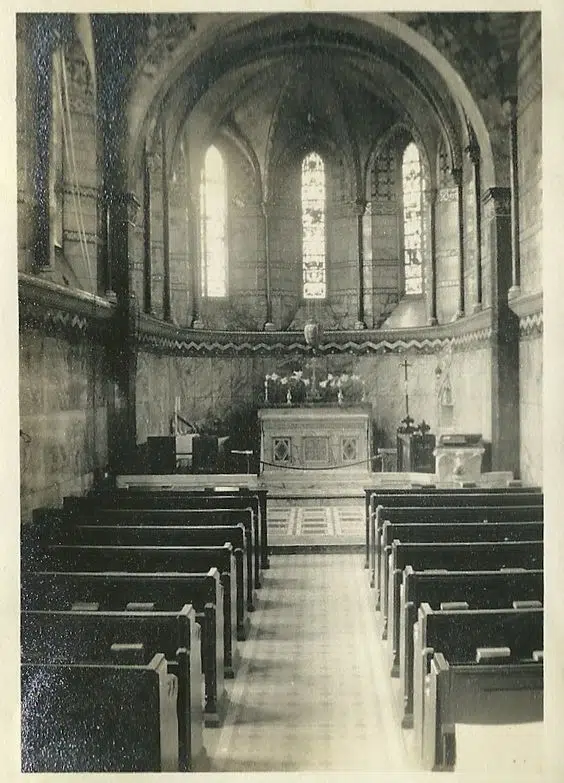

In the late 1880s, the board approached John Loughborough Pearson, one of the Victorian era’s foremost ecclesiastical architects, to design a building to suit their needs. With a confined site on which to build, the result needed to be small enough to fit, but significant in its purpose and presence. A motto attributed to Loughborough Pearson’s design process offers a question – ‘Will it bring them to their knees?’ To those of us who are familiar with the spectacular interior of the chapel, it could be a rhetorical question! The enduring beauty and significance of Pearson’s building, both architecturally and socially, gently offers an answer to his motto. Construction began in 1891 after Pearson had accepted the commission and spent months in Europe assembling materials and craftspeople to realise his design.

The decision to approach Pearson speaks of the governors’ desire to create something beyond a merely functional space. To engage one of the most renowned architects of the era to build their small chapel was a statement of intent about the quality of environment they believed the Middlesex community deserved. Funding enabling the build to go ahead in the initial stages came from several parties very keen to see a chapel built. Surgeons Lord Webb Johnson and Sir John Bland Sutton along with Mary-Anne Leicester were just a few of those who financially kickstarted the project. It was decided that no money donated or left specifically to the Middlesex should be spent on building the chapel – the rightful place for that was medical resources and patient care. As such, it fell to the Middlesex community to fundraise consistently over a period of decades in order to see the build through to completion. People fundraised for specific items: ‘Mrs X held a concert, and raised £30 to go towards paying for a candle rack’, ‘Mr Y hosted a garden party and raised £15 towards stone materials’. In this sense, the Middlesex supported the chapel in a labour of love which lasted over 30 years.

Those 115 years of community, service and sanctuary render the chapel an incredibly precious space, socially and historically as well as architecturally, and provides an ethos of welcome and acceptance which carries into our community work today.

Faye Hughes, Artistic Director

Completing the chapel

The skeleton of the chapel was in place within a relatively short space of time. However, the chapel was not complete until 1935, due in part to the fact that funding was piecemeal and it took a long time to raise money for each stage of work. It was also due to the death of the leading architect. John Loughborough Pearson died before the chapel was completed. A letter exists, dated 1897, from his son Frank to the board of hospital governors alerting them to the news of his father’s death, and stating that he was determined to finish the chapel. The detailed wall panels, floor mosaics, baptistry, window spaces and individually designed borders running around the building were all hand-set by a crew of craftsmen, including some Italian members who travelled from mainland Europe to complete the work. Renowned mosaicist Maurice Josey and his workshop created the ceiling mosaic, vaulting and roundel mosaics after Loughborough Pearson’s death, and this all took time. During the building of the chapel, the Middlesex itself underwent significant architectural work. In 1924, it was decided that the original building was structurally unsound and would have to be replaced. So while the chapel was slowly becoming the dazzling building it is today, the hospital was taken down and rebuilt around it, reopening finally in 1935.

And as the chapel, a great and gothic triumph, went up and the hospital came down, Fitzrovia once again underwent a social evolution. The wealthy began to emigrate south-westwards to Belgravia and Mayfair, forcing subdivision of the aristocratic houses into workshops, studios and rooms to let. The Bloomsbury Group moved in and launched the Omega Workshops on Fitzroy Square. As pioneering work in the medical sector took place in the hospital, in the early twentieth century, young bohemians made great changes in art, design and philosophy and drove great social change. Though not lifesaving, their radical thinking had an impact on society that continues today. Later, Augustus John, Quentin Crisp, Dylan Thomas, Aleister Crowley, the racing tipster Prince Monolulu, Nina Hamnett and George Orwell would all call the area home, congregating in pubs and renting dilapidated apartments in former mansion houses just a stone’s throw from the hospital.

Heavy bombing contributed to Fitzrovia’s fall from grace with the upper classes, and the building of social housing following the blitz increased diversity and vibrancy in Fitzrovia. Bloomsbury and Marylebone held their value as prices in Fitzrovia dropped and economic turnaround was not felt until the 1990s. The area was changeable, with a high number of properties rented and few people putting down long-term roots. Others remained in the area and stay even now. You don’t have to look far to meet present-day residents with Bloomsbury links or stories of drinking with Nina Hamnett.

Yet the hospital was thriving, with young nurses and trainee doctors beginning their adult lives in this efficient, pioneering and consistently excellent institution. This was not just a place of work, it was a place of growth, of first homes, of courtships, of marriages and the beginnings of incredible careers.

Open to all

The first service in the chapel took place on Christmas Day 1891, and from then onwards, it was used regularly by staff, patients and families of the hospital. The chapel was partially blessed by one of the bishops of London in the first few years of its existence. However, the building was never fully consecrated. This is the protocol with all hospital chapels, airport chapels and other public centres for contemplation – they must be available for anyone regardless of religion or belief. As the chapel was never fully consecrated, an inclusive variety of services reflected the livelihoods and communities engaged in serving the hospital. At times, a rabbi worked alongside the hospital chaplain, and non-denominational community leaders held gatherings here. This was taking place from the beginning of the twentieth century onwards and demonstrates the radical identity of the chapel from its earliest use in reflecting the myriad of faiths and cultures represented by its visitors. One of the first jobs of Faye Hughes, the chapel’s artistic director, when she started here was to photograph and arrange for the chaplain’s logbooks be handed over to the UCL archive to be catalogued. These were several huge books, the earliest of which dated from 1915. The handwritten entries detailed meticulously all interactions between the chaplain and the hospital community – from the services regularly held, to ward visits, rites given, and time spent with patients and families in what often must have been the hardest of circumstances.

She says: ‘Going through these logbooks was a fascinating and moving window into the routine and significance of the chapel within the hospital. Along with the commemorative plaques in the narthex, they provided a small sense of the scale and significance of activity which went on in this golden building. Through meeting medical staff who have returned to the chapel for visits and reunions, over the last three years I have learned much about the role the chapel played for staff – from Christmas nativity services featuring multiple infants and mothers from the maternity wards, to concerts held by the hospital choir, and also as a place of regular quiet contemplation or solace. Many nurses have spoken movingly of how the chapel offered a place of reflection and peace for young staff, even if only for five minutes at the end of a particularly difficult shift. Others have told me about bringing patients down to the chapel as a momentary retreat from the bustle of the ward, and still more people have mentioned swiftly organised weddings which took place between terminally ill patients and their partners in the chapel. I met a nurse and doctor who became engaged in front of the altar and recreated their engagement for a photograph during their visit back. Through the memories of visiting ex-medical staff, I have become more familiar with significant elements of hospital life – memories of the iconic Sister Eleanor Bender abound amongst every nurse who trained during her tenure, so often has she been spoken of during visits. I learned about the tunnels running beneath the building, and the part myth, part hopeful joke among some training nurses about a hidden side tunnel which, when followed, would bring you up behind the bar of the King and Queen at the other end. Hearing about the Acts of Mercy paintings by Cayley Robinson which are now on display on rotation in the Wellcome Collection, and the tiles from the childrens ward which were saved and are now on display in the Jackfield Tile Museum in Ironbridge painted a picture for me of the passion held by the Middlesex Hospital community for their environment. It has been wonderful to meet so many members of that community and be able to welcome them into the preserved and restored chapel. The significant milestones of lives spent in industrious team efforts and strong community are the heart of the chapel’s history and meeting the people who populate that history has been a joy. The chapel stood within the hospital for 115 years, from its genesis in 1890 through to the final period of the hospital’s existence in the early 2000s. Those 115 years of community, service and sanctuary render the chapel an incredibly precious space, socially and historically as well as architecturally, and provides an ethos of welcome and acceptance which carries into our community work today.’

And yet, despite the significance to so many, the chapel was little known to the community outside of the hospital. It was not for them. Its magnificent design and value to those working or visiting the hospital was not felt by those on the other side of the hospital walls. This beautiful, remarkable building was hidden from view. Many were entirely unaware of its existence.

In 2005, the main hospital building had been declared unfit for use. It had already been rebuilt once in the 1930s, and to do this again was not a financially viable option for the NHS. The NHS sold the land, and a development period began which was elongated by the effects of the financial crash of 2008. When a developer finally took over the site, it was agreed between them and Westminster Council that the developer should contribute towards restoring the building, and that as a very precious Grade II* listed heritage site the building should be handed to a charitable foundation set up with objectives which could serve the local community through access to the arts, a space for wonder and peace, and to ensure preservation of the building.

As the hospital came down, the chapel was propped on stilts and stood in a wasteland of mud before building began. This hidden gem was briefly exposed and stood, looking vulnerable, abandoned in the middle of a building site. For the first time in its history, it could be seen by the community of Fitzrovia. By its neighbourhood.

Restoration and residents

Restoration took place between 2013 and 2015, which saw water ingress problems solved, mosaic repairs to sections of ceiling, a small extension added to provide a kitchen and bathrooms, and a new lighting system installed in the chapel which lights the mosaics and stonework to magnificent effect. The golden ceiling, which for a century had received limited daylight and was lit internally only by candles, was now splendidly visible, having been restored with immense care, At the end of 2016, a new community arrived in the chapel – within its organ loft specifically, which is the office space from where the chapel foundation is run. An Artistic Director was engaged by the board of trustees to oversee the day-to-day work of the foundation, and a small team came into being who run the building as a venue and manage the charitable activities which connect us with the wider community of Fitzrovia. This community has grown to include volunteers, many of whom are ex-medical staff, and many more people who came to know the chapel for the first time, and who now recognise it as part of their local landscape. Westminster Arts, the American Soup Kitchen and All Souls local primary school are just a small handful of the new connections made in this chapter of the life of the chapel, as well as many local residents. And we maintain as our pilot light the original ethos of the chapel as a welcoming place of sanctuary, a place for communities to celebrate, to pause or to find peace for a moment in a constantly busy world. Our first exhibition, called The Ward, focused on the hospital community and its work in leading the way with HIV and AIDS care in the early nineties, and our subsequent exhibition called Dwelling celebrated the lives of those living and working in our immediate environment. We have made many friends and new connections in our creative and community work thus far, and it is exciting to see this continue. Our remit is our local community, offering creative and reflective opportunities for wonder, peace and contemplation. The need for space to reflect on lives and experiences can have no more perfect, peaceful and glittering example in London than this chapel.

We were challenged with finding a place for the chapel in its new community – a community of social housing, of some of the highest poverty rates in London, a strong community of counter-culture artists and collectors, a thriving socialist and left-wing community, home to big business and dynamic development and a daily surge of commuters. For the third time, this remarkable building has found itself at the centre of great change.

To make plans for its future, we looked back. To us, the chapel’s most compelling stories come from those who worked in the midst of it all: the nurses who stopped by in the middle of their shift to take a moment for themselves, the hospital porter who slept on a pew in exhaustion, the bloodied surgeon who took a minute between operations.

We acknowledge the impact of a space like the chapel; we follow John Loughborough Pearson’s intentions in its new purpose.

We invite the chapels new community for a moment’s respite, an opportunity to experience something beautiful, remarkable and away from the everyday. To reflect and quietly contemplate. A radical thing in a busy city. Our visitors may not step out of the operating theatre or come off a night shift, but they visit us from the bustling streets of central London, the state schools, the office blocks. We open our doors to everyone and give them the opportunity to glimpse something truly beautiful. In doing so we honour the past, the intentions of Major Ross and respond to the radical changes felt by this radical building.